Connecting the Dots

- carolcosman

- Mar 14, 2021

- 3 min read

“At no point in my career or life have I felt our nation’s values under greater threat and in more peril than at this moment. Our national government during the past few years has been more reminiscent of the authoritarian regime my family fled more than 40 years ago than the country I have devoted my life to serving.” - Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman (Ret.) The New York Times — August 1, 2020

When news stories become ancient history within days of their release, some news is still worth revisiting, weeks, months and even years later. Last summer, Alexander Vindman wrote an op-ed article for the New York Times that struck me on a visceral level. This connection has to do with family history. My family had fled the same country as his decades earlier for the same reasons; to live better lives free of authoritarianism and injustice. As I watched Vindman’s testimony in front of the House Judiciary Committee in October of 2019 preceding President Trump’s impeachment, it became abundantly clear to me that our democracy is, indeed, fragile and we must stay vigilant to safeguard it.

I can only imagine the hurdles his father had to overcome, a widower with twin three-year-old sons trying to keep his family safe. Alexander’s father’s generation had lived through the refusenik and dissident movements of the 1960s through‘80s. These refuseniks and dissidents were Russian citizens who turned their attentions to issues relating to freedom of expression, conscience, and the right to emigrate. Through underground samizdat publications and defiant public gatherings, dissidents rebelled against government regulated psychiatric prisons, unwarranted arrests, and the horrifying treatment of political prisoners.

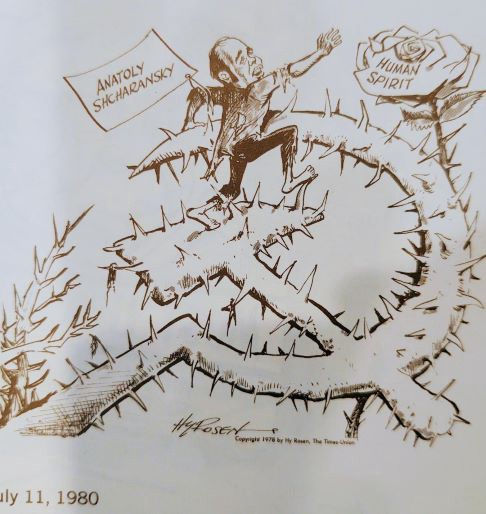

I grew up in a family and community where activism for Soviet refusenik and dissident causes influenced me later in life. In the 1970s, my mother welcomed families like Vindman’s and helped them settle into our community. My uncle was a syndicated political cartoonist and when extended family got together for Thanksgiving, Passover, or New Years’ meals, heated discussions among the grown-ups would fly back and forth across the table ranging in topics from the latest local and state news to international issues of the day. Opinions were strong, and I, like my sisters and cousins, would try to make sense of it all.

On a larger scale, demonstrations and marches in cities all over the U.S. and around the world showed the Soviet government that they would be held accountable for human rights violations. Organizations such as The Action Committee for Soviet Jewry, Israel’s Liaison Bureau, and other international human rights organizations raised money for and found ways to communicate with dissidents and refuseniks. The U.S. Jackson-Vanik amendment of 1974 restricted trade agreements with any country who violated citizens’ basic human rights, and right to emigrate.

As a young adult, I turned to a career in music, but the values that influenced me growing up — advocating for social justice and human rights never left me. Later, when I became a writer, these issues found their way into my historical novel Dissonance. I wholeheartedly agree with Alexander Vindman when he so eloquently explained in his op-ed, “America has thrived because citizens have been willing to contribute their voices…to challenge injustice and protect the nation…To this day, despite everything that has happened, I continue to believe in the American Dream. I believe that in America, right matters. I want to help ensure that right matters for all Americans.” Following his words, we must continue to uphold our democratic principles and institutions so that we remain the beacon of hope for people like Alexander’s father.

Comments